What Is VistaVision?

INTRODUCTION

Many, many decades before full frame cameras became all the rage, VistaVision emerged as the original, old school, magical, large format option. Influencing everything from camera design to the way modern cinematographers think about resolution and texture.

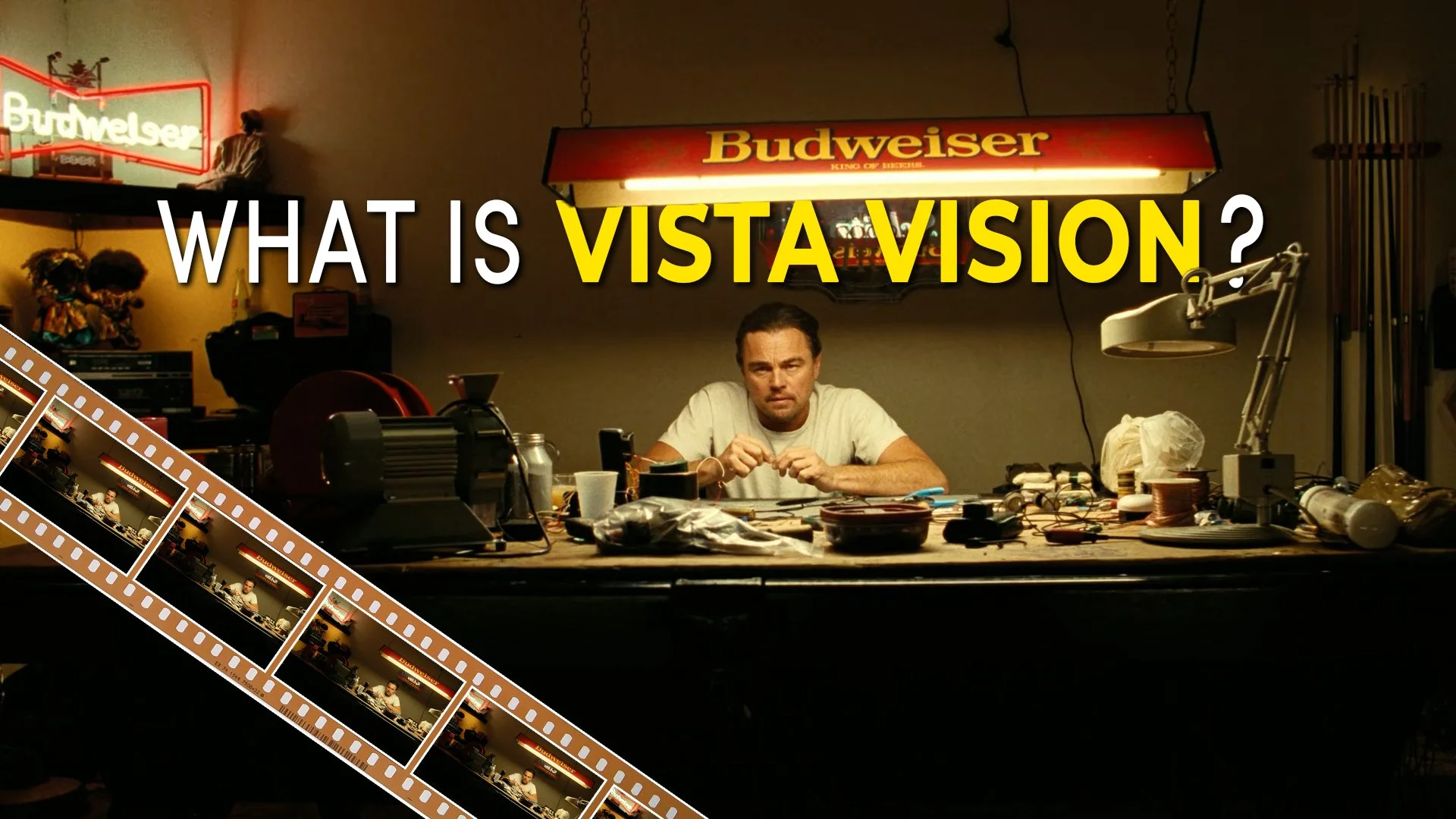

But despite its vintage roots, VistaVision has quietly re-entered the modern filmmaking landscape through an influx of new movies shot on this 35mm film format.

So in this video, we’re going to look at what VistaVision actually is, why it disappeared, and why it’s suddenly everywhere again.

HISTORY OF VISTA VISION

VistaVision was introduced by Paramount in the 1950s as a premium theatrical exhibition format.

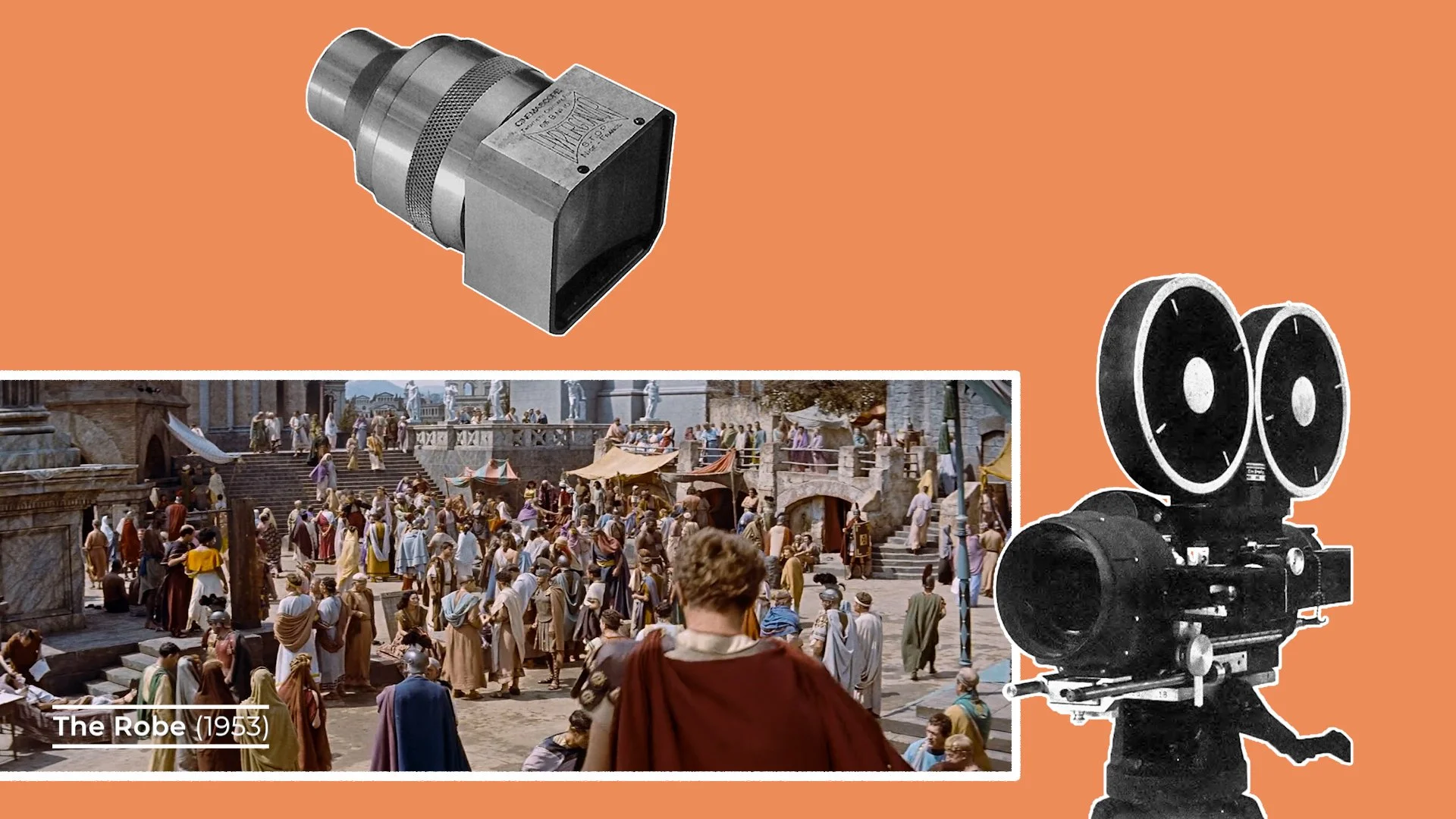

At the time, Hollywood was in a technological arms race with movie studios experimenting with wider, sharper, more immersive 35mm images - on formats like Cinemascope which used anamorphic lenses to get a wider aspect ratio.

They hoped these new formats would pull audiences back into cinemas, after attendance massively declined with the invention of home viewing on TVs.

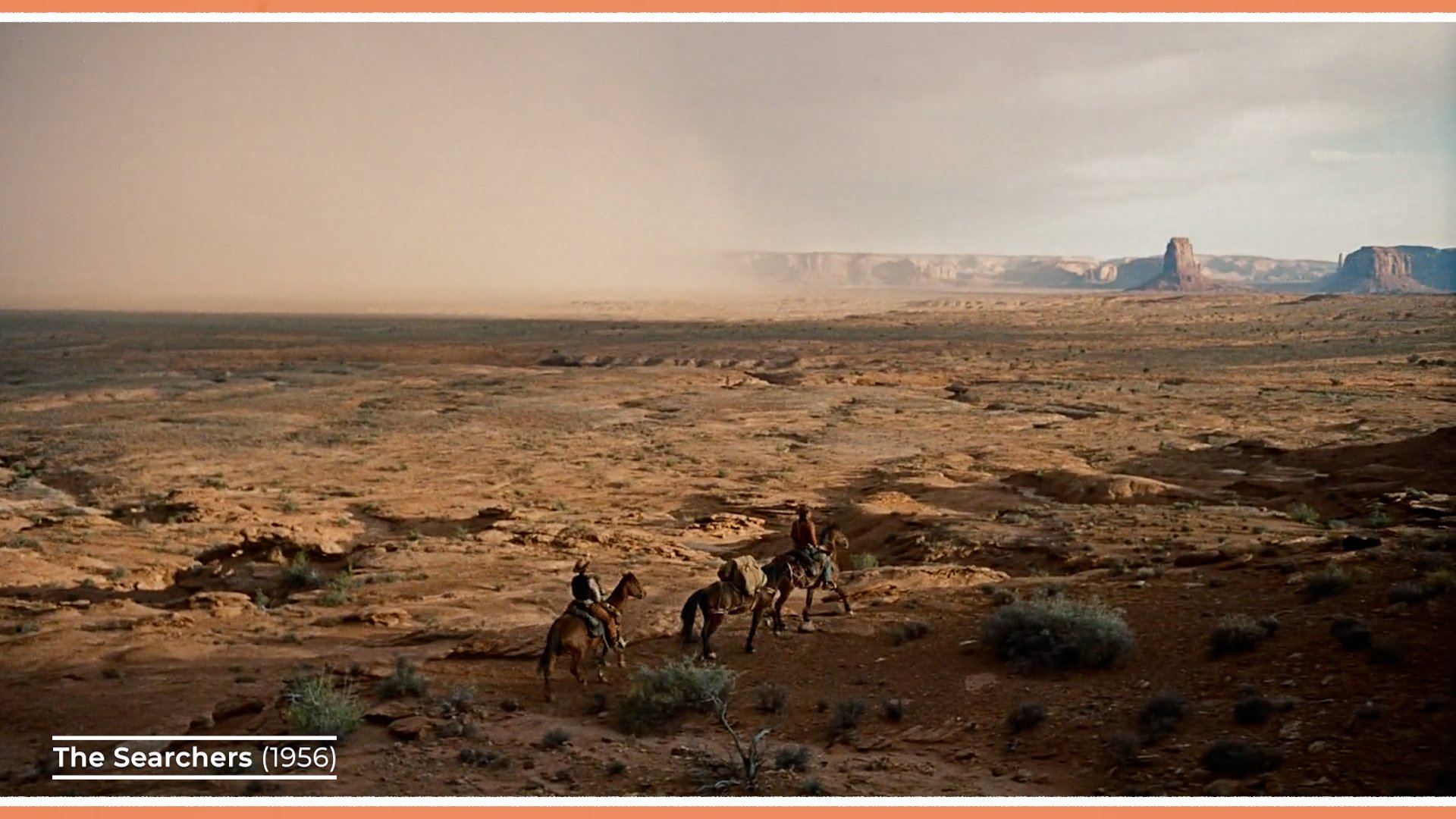

For a while, VistaVision delivered that larger than life, enticing visual experience with higher resolution, wider field of view images. Films such as Vertigo, The Ten Commandments, North By Northwest and The Searchers made full use of the format’s clarity.

But as the ’60s and ’70s arrived, VistaVision’s popularity declined. New widescreen formats, cost pressures, and the success of anamorphic 35mm meant that VistaVision workflows became too expensive and too cumbersome for most productions. And so, the format faded away.

However, I think cinema technology is kind of like fashion in that preferences for different technical gear often goes through cycles. And, much in the same way that TV in the 50s challenged cinema’s dominance, I’d argue that so too has the recent rise of streaming services forced studios and filmmakers to seek out larger than life exhibition formats and viewing experiences like Imax, or VistaVision to try to draw audiences back to the cinemas.

From 2024, VistaVision saw a small but meaningful resurgence. Films like The Brutalist, One Battle After Another, and Bugonia embraced it as a deliberate creative choice that provides those tactile qualities and large-format characteristics that are unique to VistaVision.

WHAT IS VISTA VISION

But why is VistaVision different and how does it technically work?

In order to understand this larger film format we first need to know how regular 35mm film capture works.

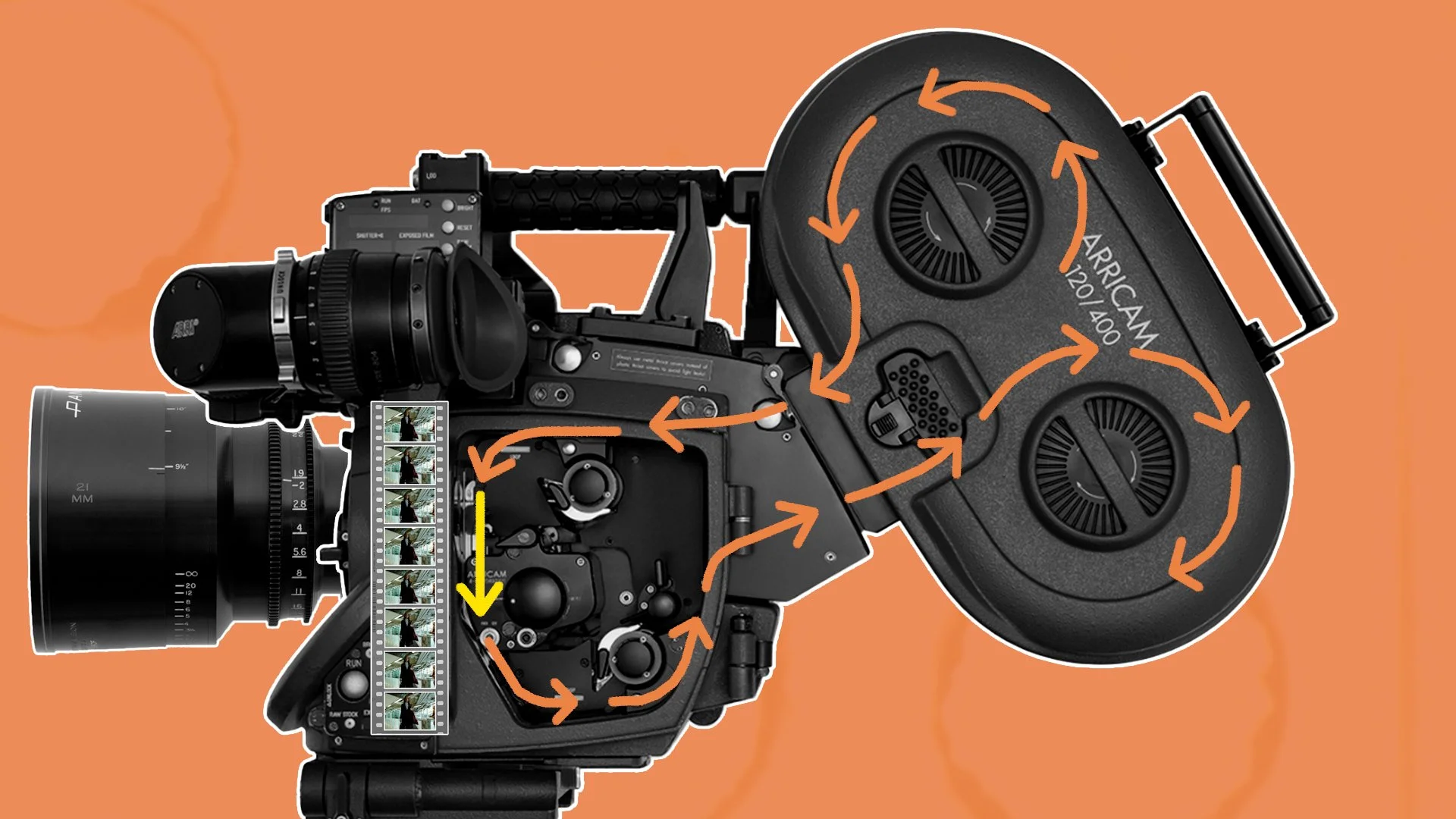

Normal 35mm cameras store film stock in what’s called a magazine. When the camera rolls, the unexposed film exits the mag, and passes vertically through a film gate where each frame is captured, before the exposed film is then stored once again in the magazine. The regular Super 35 format captures each image in a frame that is 4 sprockets or perfs tall.

VistaVision uses the same 35mm film, but captures each frame in a different way.

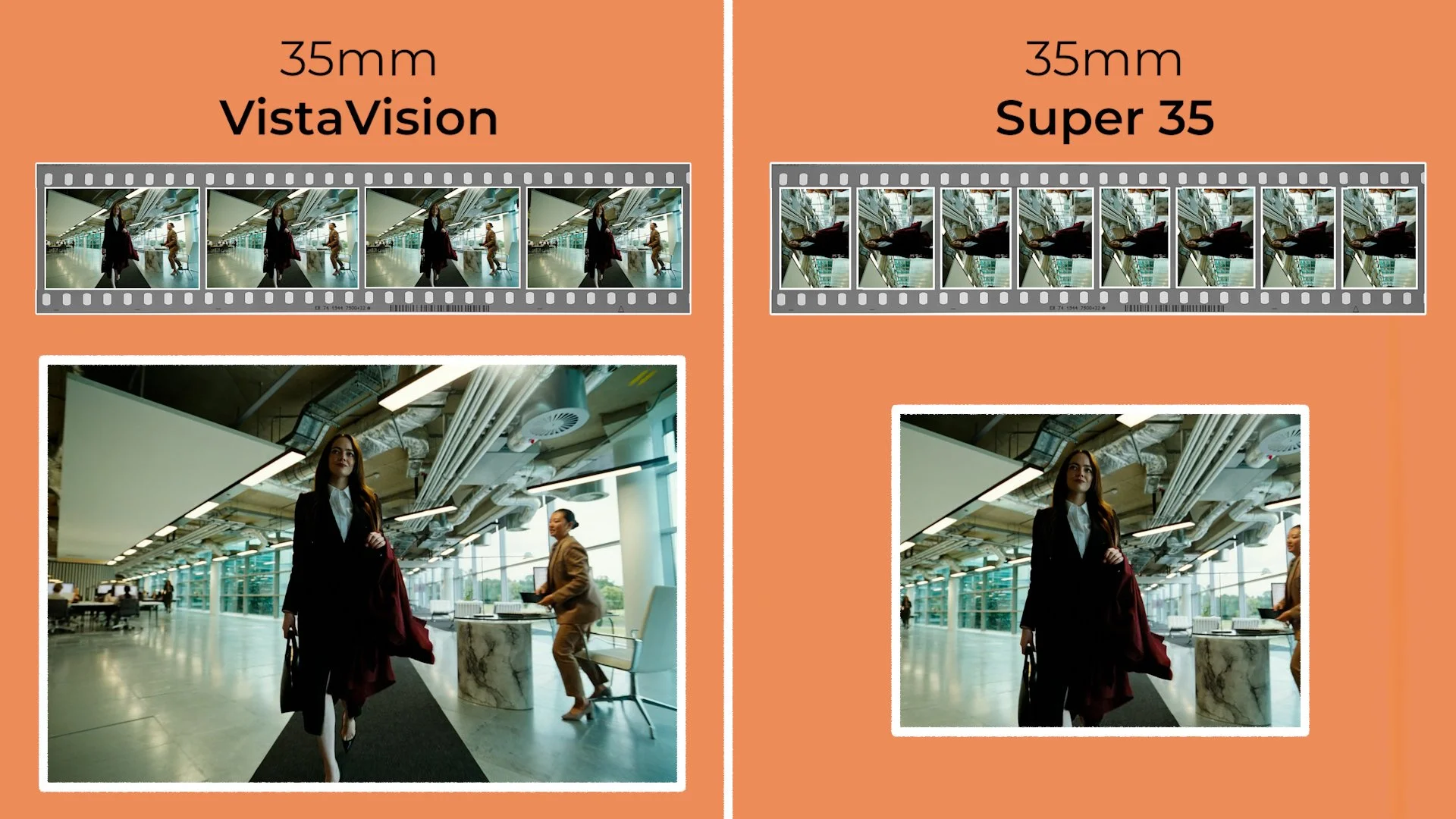

Instead of running the film vertically through the gate, it moves across the film plane horizontally. By feeding the film sideways, VistaVision is able to capture frames that are eight perforations long, which is roughly double the size of a standard Super 35 frame.

This is why VistaVision cameras look so distinctive. The film magazines are rotated 90 degrees compared to a typical 35mm camera, so that the magazine sits horizontally, feeding the film laterally across the gate.

That’s the essence of VistaVision: the same 35mm film - just used in a different orientation to maximize the negative size.

VISUAL CHARACTERISTICS

The appeal of VistaVision isn’t just technical: it’s mainly due to the visual traits it comes with.

Because the negative size is physically larger than Super 35, more information is captured over a bigger area. This means that VistaVision offers exceptionally good clarity, detail and a highly resolved image.

Because of this high resolution, which helps with special effects, it was used as a specialist camera to shoot miniatures, such as on Star Wars, many decades before high resolution digital cameras were a thing.

When this high fidelity film image is scanned or projected the grain structure will appear tighter and less apparent due to the increased image area. Even high-speed stocks filmed in low light situations will have a slightly cleaner texture than Super35.

A secondary effect of this larger negative is that it yields a naturally wider field of view at equivalent focal lengths. For example, if you shoot a frame on a 50mm lens with a VistaVision camera and with a Super35 camera and place them next to each other, the Super35 frame will be about 1.5x narrower than the larger format image.

Practically this means that you can shoot on slightly longer focal length lenses and still maintain an expansive perspective, while getting the added benefit of a shallower depth of field, even in wide shots. Which many find to be quite a cinematic look.

Or, if you put a wide angle lens on a VistaVision camera, then it’ll expand the space even more. That’s part of why this format feels so immersive and dimensional.

Like a 35mm stills camera, the native VistaVision frame is closer to 1.5:1 or 3:2. Which is a slightly squarer frame with more height. Historically it was often cropped or optically printed to widescreen ratios like 1.85:1. Although occasionally some movies, like the recent Bugonia, decided to stick to the original 1.5:1 ratio of the negative.

Modern productions shooting VistaVision which will be finished with a digital post production workflow can choose almost any delivery aspect ratio while retaining the format’s inherent resolution advantages.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

For all its beauty, VistaVision comes with trade-offs.

VistaVision cameras are big - much larger than standard 35mm motion picture camera bodies. Their horizontal magazines add bulk, and the film transport mechanism requires space.

There are a couple different types of these old VistaVision cameras - like the Wilcam W-11. This camera is especially large and heavy, which means they are basically only designed to be used on a camera platform like a dolly or on a tripod.

One reason for the W-11’s bulk is that it's blimped. This means that when the motors run the film through the camera it is quiet enough to still record sync sound dialogue.

There is another slightly smaller and lighter VistaVision camera made by Beaumont. Although it’s a bit smaller than the Wilcam it’s still pretty enormous by modern digital cinema camera standards.

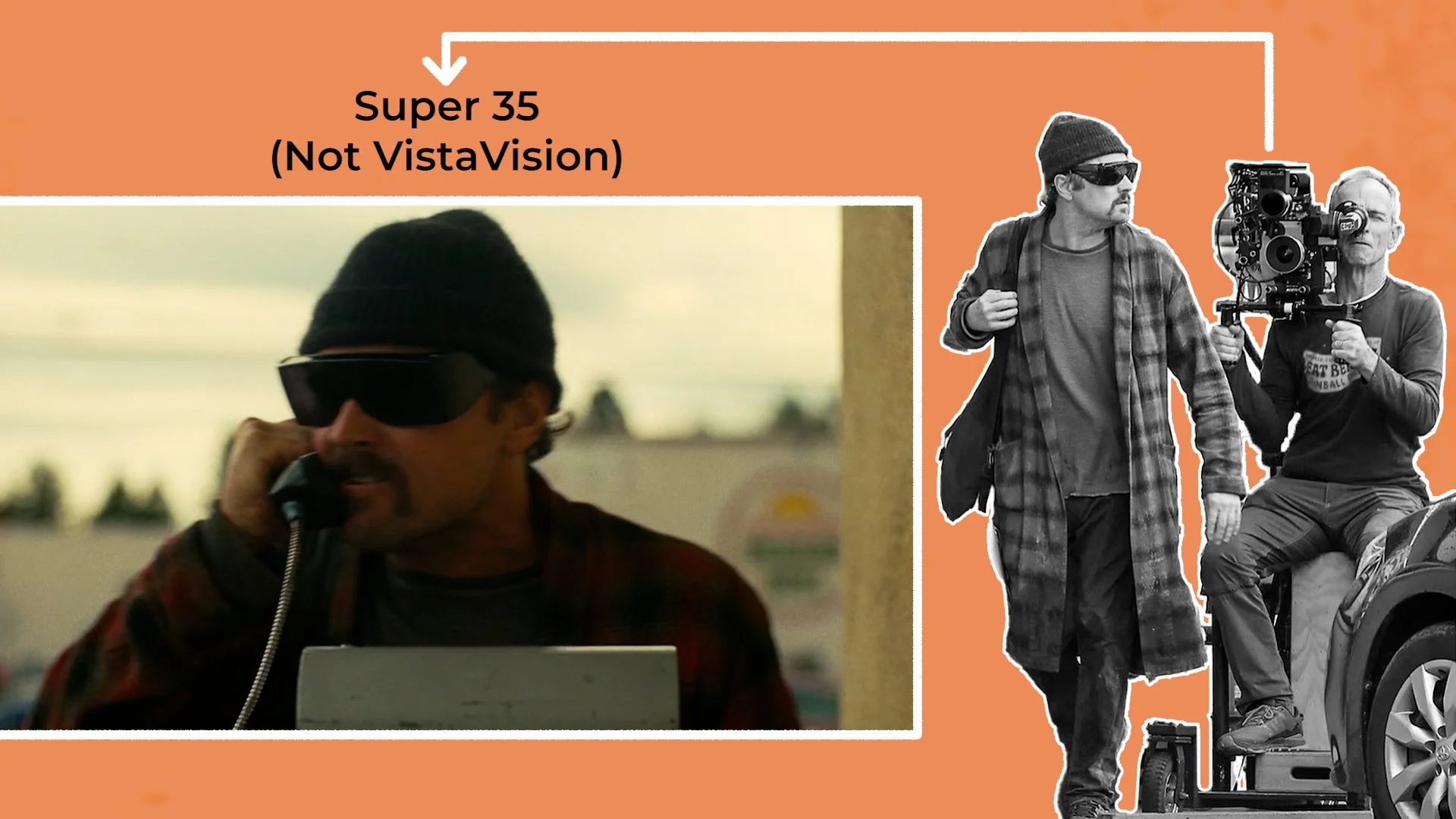

It is technically possible to shoot handheld or mount these Beaumont cameras to other grip rigs like a stabilised head or a car rig, yet their large size still makes it pretty impractical and challenging to do so.

A trade off for this smaller form factor is that these cameras are excessively loud, which makes it difficult if not impossible to record usable sound for dialogue scenes - especially indoors.

Another practical downside, which cinematographer Robbie Ryan spoke about, is these old cameras tend to get jams from time to time where the 1,000 feet of 35mm film flying through the camera gets stuck. If this happens it means the take will have to be aborted and started again.

The larger frame means standard Super 35mm lenses will not cover the VistaVision image area without vignetting. Cinematographers have far fewer lens options to choose as they are forced to select from glass which has sufficient coverage, often pulling from specialized large-format or vintage glass sets.

On top of tracking down the lenses, the rarity of these VistaVision cameras themselves can make them very tricky to source. Their age also means most of these cameras don’t have modern features like a good video tap - which means directors and DPs may not be able to view a clear image of what they will shoot on a monitor.

Because the VistaVision negative is twice as large, you burn through 35mm film stock at double the rate. Every take costs more and every reload is more frequent and the length of the takes you can shoot with one magazine is shorter. The budget implications can therefore be a serious consideration.

CONCLUSION

VistaVision sits at a fascinating intersection of old and new - born from mid-century innovation, abandoned for decades, and now rediscovered by modern filmmakers searching for a specific kind of cinematic texture.

It’s a reminder that film technology isn’t a straight line of progress but a series of cycles, with each generation finding new meaning in old tools. And as long as filmmakers continue exploring the expressive potential of the format, VistaVision will remain a powerful - if niche - option for creating images that feel both timeless and unmistakably tactile.