Understanding Focal Length In Cinematography

INTRODUCTION

When you watch a movie, you’re not just looking through a camera, you’re looking through a lens that has a specific viewpoint, a specific way of interpreting depth, scale, and distance. And that viewpoint, expressed as a focal length, affects everything.

Today, we’re going to explore what focal length actually is, how it works, how different formats can change the field of view, how focal lengths shape emotion, and most importantly how filmmakers can use lenses as creative tools.

WHAT IS FOCAL LENGTH?

At its core, focal length is a measurement for each lens, usually written in millimetres, that affects how wide the image feels, how compressed or expanded the space is, and how connected, or distant, the audience feels from the characters.

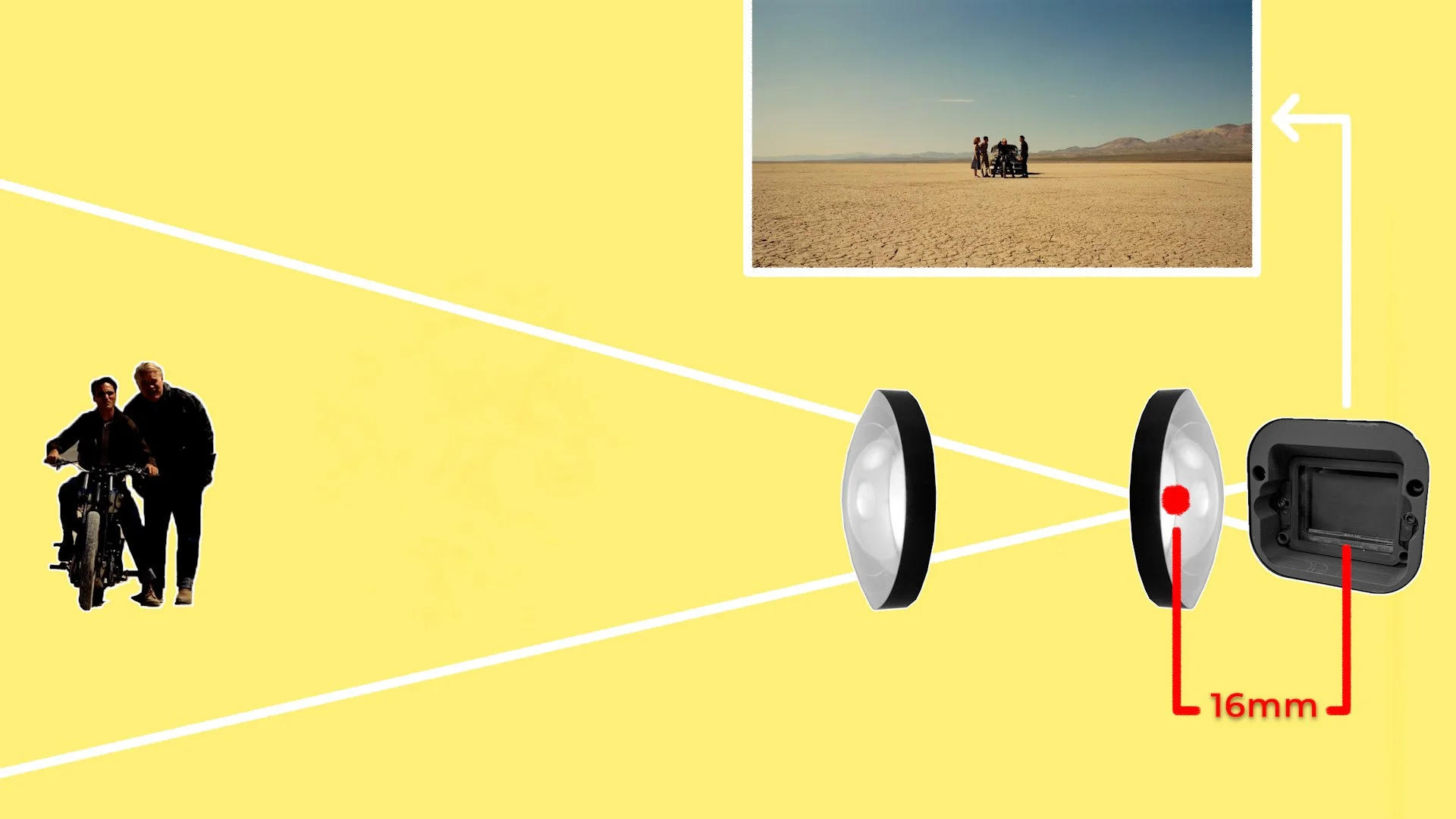

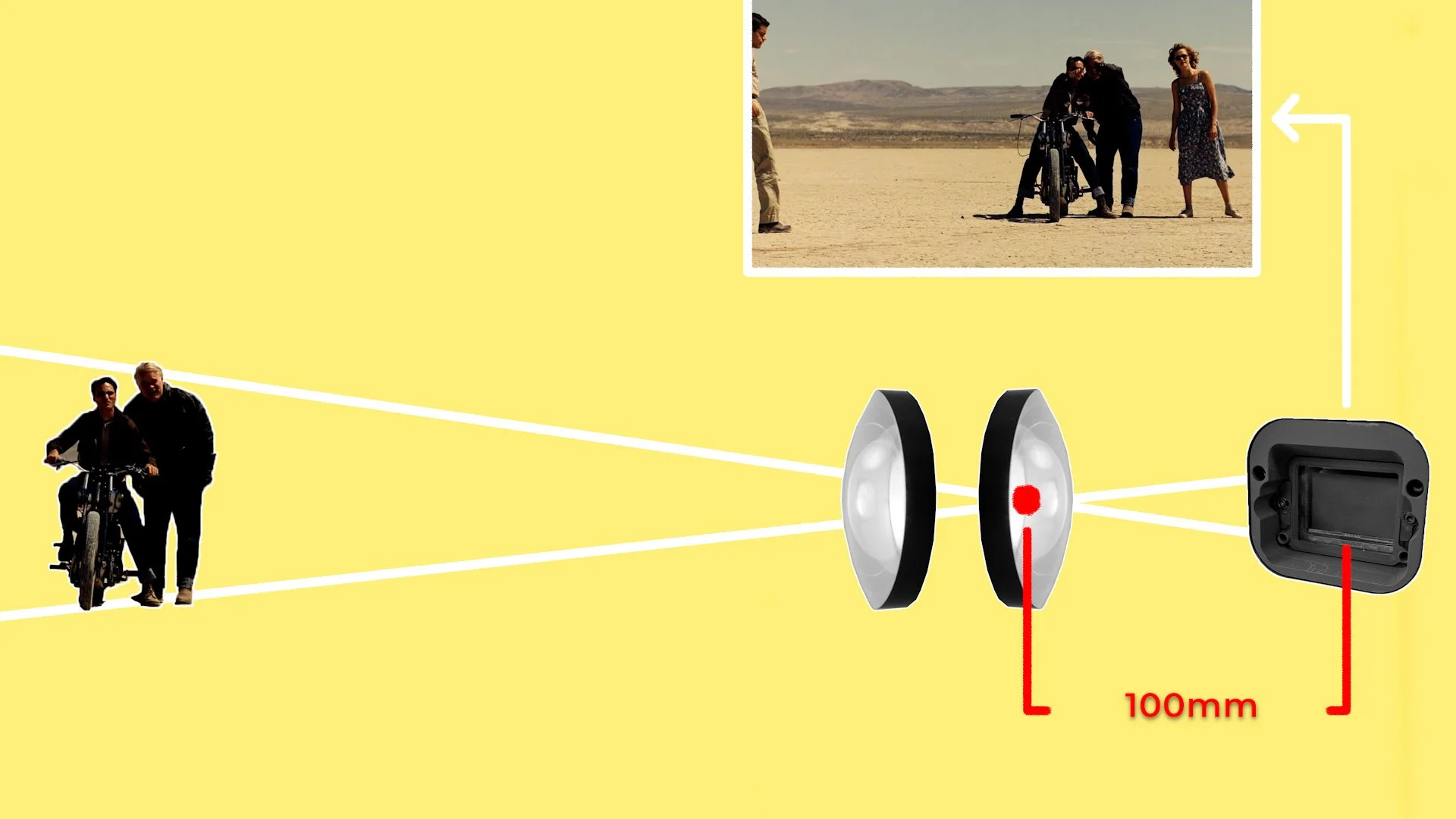

Inside every lens are glass elements that bend and converge light. When these elements bring incoming light rays to a point of focus, that point has a physical distance from the sensor.

Focal length is therefore calculated as the distance between the optical centre of a lens and the camera’s sensor or film plane when the image is in focus on objects far away at infinity.

A shorter focal length, such as 16mm, bends light more strongly, producing a wider field of view. While a longer focal length, like a 100mm, bends light less, producing a narrower field of view.

This physical behaviour becomes the foundation for the visual language of wide angle, normal, and telephoto lenses.

WIDE ANGLE LENSES

Wide angle lenses, all the way from a 6mm fish eye, to 18mm, 24mm, or 25mm focal lengths, capture more of the environment with a wide field of view. They stretch space, exaggerate distance, and make movement across the frame feel more dynamic and easier to track by a camera operator.

When the camera is placed physically closer to the subject, such as when getting a close up, wide lenses create a sense of immediacy. Faces feel more intimate, the world feels larger, and motion feels alive.

However, because of how these wide lenses bend light, it may also start to distort spaces or people’s faces in an unnatural, exaggerated way, especially as the lens gets closer to the subject.

MEDIUM LENSES

Lenses around 35mm to 50mm sit in a sweet spot that feels natural and what we call a medium, normal or standard focal length. They don’t distort space too much like wide angle lenses do, nor do they compress it too heavily like telephoto glass does.

A 35mm gives a slightly wider, more energetic perspective, while a 50mm often feels clean, honest, and somewhere around what we associate with the natural field of view of how our eyes see the world.

Filmmakers often use these focal lengths when they want the audience to feel like an observer rather than a participant, on wide angle lenses, or a voyeur, on telephoto lenses.

TELEPHOTO LENSES

Telephoto lenses, such as 75mm, 100mm, 135mm all the way to 200mm zooms and beyond, compress space and offer a much tighter field of view. This means that to get a similar width to the frame of a wide angle or medium lens, you’ll need to move the camera much further away from the subject.

Not only does this make the footage feel more voyeuristic, but it also establishes a more voyeuristic relationship between the person on screen and the camera operator.

This spatial relationship may not always be desirable, such as when filming a sit down interview, where you may want the person asking the questions to be closer to the subject and able to empathise and interact with them more personally and casually, rather than shouting from across the other side of the room behind a telephoto lens.

Objects captured by telephoto lenses appear closer together. So backgrounds can be made to seem much nearer to characters than they are in reality. This can be used for moments of action or to make dangerous objects or animals appear like they are right next to the actor.

Backgrounds blur into soft washes of colour, and characters feel isolated from their surroundings.

These lenses flatten depth, slow down the feeling of movement, and often create a sense of tension or emotional distance.

Focal lengths come with another practical effect. The longer the lens is, the shallower depth of field it will have. Therefore, wide angle lenses will have a less blurry background, and be much easier and more forgiving to pull focus on and keep the subject sharp. Telephoto lenses will have a much softer, more out of focus background, and are much trickier for 1st ACs to accurately keep moving subjects sharply in focus.

CREATIVE USES OF FOCAL LENGTHS

Focal length isn’t only about technical behaviour. It’s a creative choice that can be used by filmmakers to subtly support and add to the visual storytelling.

Emmanuel Lubezki is famous for his extreme use of wide-angle lenses. Often for directors like Alfonso Cuarón, Terrence Malick and Alejandro González Iñárritu. In films like The Revenant, Children Of Men, and The Tree Of Life, he often uses 12mm, 14mm, or 18mm lenses which yield an incredibly wide field of view which often leads to faces distorting when framed for close ups.

Because of this extra width, camera bumps and shakes will be less prominent and noticeable - which makes these wider lenses better for smoother, less shaky handheld footage.

By seeing more of the background, the world becomes a character. You sense the cold, the terrain, the vastness, or the cityscape. The camera can move intimately close to actors while still preserving context - partly because of the expanded view and partly because wider lenses have a deeper depth of field where the background will be less blurry and soft and still distinguishable. Wide lenses dissolve the barrier between the audience and the scene, creating an almost first-person feeling.

The purpose isn’t just to go wide. It’s to bring the viewer into the environment and make the footage feel more immersive and subjective.

This technique is certainly not bound to one cinematographer, and has been used early on by directors like Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, or later, by Wong Kar-Wai, to visually exaggerate and distort faces, spaces, motion and emotion.

Moving a little tighter to more medium focal lengths like a 35mm or a 50mm - we have filmmakers who prefer to photograph in more of an objective and natural style.

Yasujirō Ozu famously preferred the 50mm lens and would use it almost exclusively in most of his movies. To him, it was the closest approximation of how humans perceive the world: simple, respectful, and honest.

He didn’t want to impose perspective onto the audience. Instead, he wanted the camera to observe, quietly and truthfully, as life unfolded.

A 35mm has been used to create a similar naturalistic window into the world in films like Call Me By Your Name, or a similar 40mm lens on Son Of Saul.

On the furthest end, the Safdie Brothers have mainly used long telephoto lenses for a completely different emotional effect: from 75mm to 360mm anamorphics or even a ridiculously long Canon 50-1000mm zoom.

In films like Good Time, Heaven Knows What, or Uncut Gems telephoto glass creates a compressed, chaotic, almost claustrophobic world.

Characters feel boxed in. Backgrounds crowd them from all sides and are blurred so that the characters are the sole focus.

This tension becomes part of the storytelling, and feeds into the traits of the characters and fast paced trajectory of the plots. Every shot feels like it’s vibrating with nervous energy.

Michael Mann is another director who consistently uses telephoto lenses, especially in urban environments in action thrillers like Heat or Collateral. Often favouring a 75mm or longer.

These lenses compress and isolate characters and create a visually tense, voyeuristic filmmaking language which creates a feeling of surveillance, alienation, and existential pressure. Making his characters appear trapped inside dense urban grids, like they are always being watched and moving through hostile spaces.

FORMATS & FOCAL LENGTHS

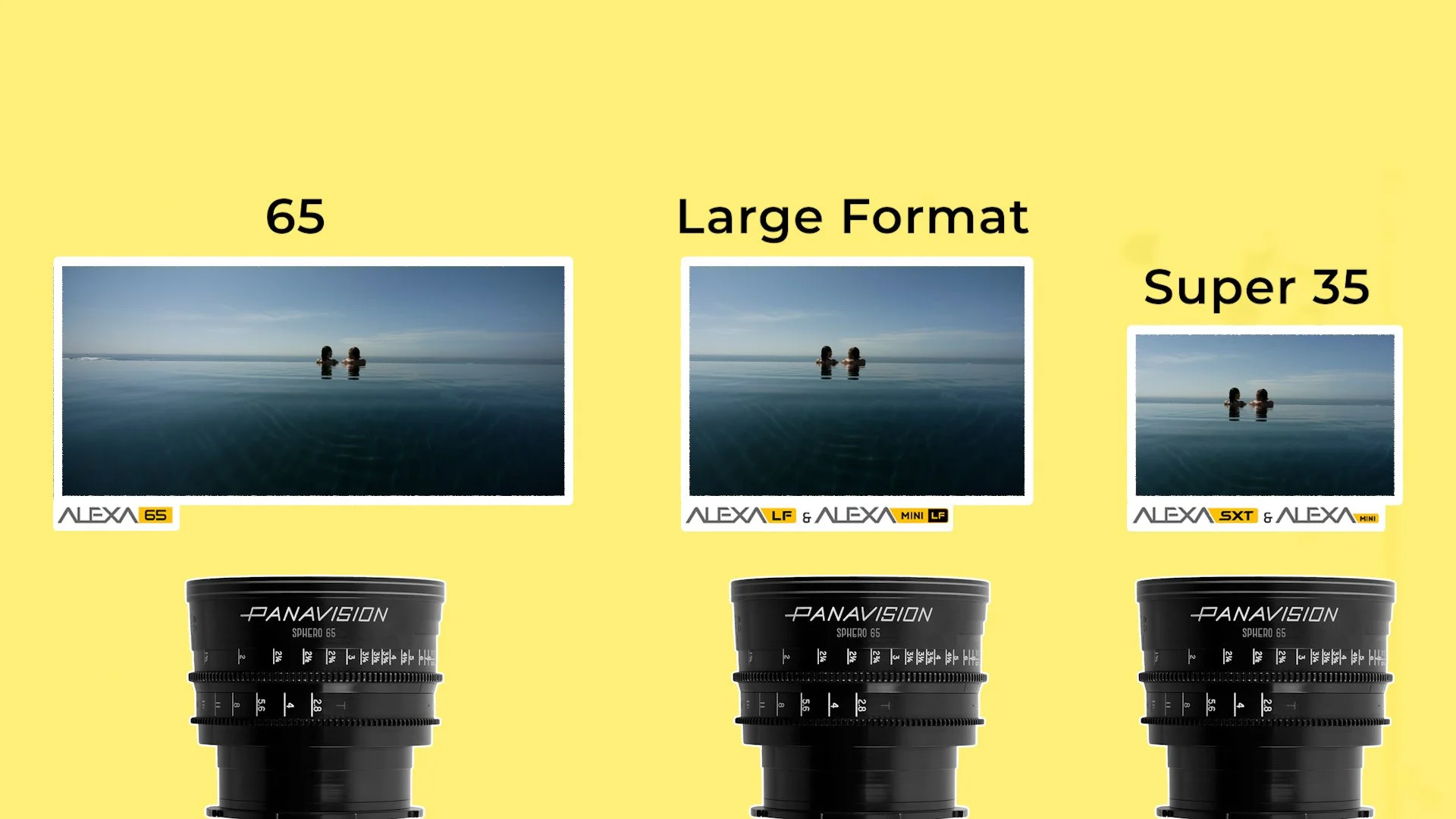

A final note is that the same focal length can yield a different wider, or tighter field of view when they are used on cameras with different format sensors or film gauges.

Super 35, whether on film or with cameras like the Alexa Mini or 35, is the traditional cinema standard. This format is usually what cinematographers have in mind when they think about the field of view of a focal length.

In comparison, 16mm film or similar sized sensors have a relatively small image area. Lenses therefore appear longer and images more cropped in. This gives 16mm its signature tight, intimate, energetic feel.

Full frame digital and large-format film captures a much bigger image area. Lenses therefore appear wider on these sensors. This format gives footage a sweeping, spacious feel with a very shallow depth of field, and portraits that have a sense of scale.

The focal lengths of the lenses themselves don’t change when they are put on different cameras, however smaller or larger sensors will just reveal more or less of the lenses field of view.

So, a 35mm focal length on a Super 35 camera will have approximately the same field of view as a 25mm lens on a 16mm camera, which should also be similar to a 50mm lens on a full frame sensor.

CONCLUSION

Filmmakers choose focal lengths not just to capture images, but to create unspoken meaning, to shape perspective, to draw the viewer in or push them away, to make characters feel vulnerable or powerful, connected or isolated.

The more deeply you understand focal length, the more you realise that every shot carries an emotional weight determined not just by what you point the camera at but by how you choose to see it.