How The Safdies Shoot A Film At 3 Budget Levels

INTRODUCTION

Josh and Benny Safdie are independent filmmakers with a filmmaking language that’s instantly recognisable: abrasive sound design, telephoto lenses, real locations, and stories driven by panic, desperation, and momentum.

Across their work, they return to characters trapped by bad decisions, narratives unfolding at breakneck speed, and urban environments that feel hostile and claustrophobic.

In this video, we’ll look at how the Safdie Brothers made the lower budget Heaven Knows What, the medium budget Good Time, and the higher budget Uncut Gems - examining what aspects of their filmmaking changed as the budgets grew, and what remained fundamentally the same.

HEAVEN KNOWS WHAT – LOW BUDGET

Heaven Knows What represents the Safdie Brothers at arguably their most stripped-back and uncompromising.

The film is based on the real-life experiences of Arielle Holmes who also stars as a fictionalised version of herself. Josh Safdie first met her on the street while doing research in the diamond district for a bigger movie they wanted to make later called Uncut Gems. After first meeting to potentially cast her as a shop assistant in Uncut Gems, he later realised there was another, more autobiographical film to be made about her life.

“I started to commission Arie to write about her life. She blew me away with these writings which were so immediate and so cinematic.” - Josh Safdie

The brothers then adapted this into a story formed for the screen which depicted: homeless youth, a romantic relationship, addiction, and street life in New York City.

The budget for the film, which came from the production company Iconaclast, was fairly bare bones, and the production reflected this at every level.

The Safdies shot almost entirely on real locations, using non professional actors and available light wherever possible. The crew was minimal, the gear footprint relatively small, and the approach was highly reactive. Scenes feel like captured reality rather than being staged, with the camera often struggling to keep up with the characters.

The Safdies enlisted DP Sean Price Williams to shoot the film.

“We talked about the movie being an opera of long lens. We always looked at the movie as an opera and wanted to do as much as we could to combat a documentary vibe. So no handheld. We shot the whole movie on tripods.” - Josh Safdie

Shooting in this way was perhaps a bit counter intuitive. As standard practice would be to create more of a vérité documentary style realism with a handheld run and gun aesthetic.

Instead they treated the situation almost like filming a wildlife show, by placing the camera very far away from the actors where they wouldn’t be noticeable, in public spaces on the other side of the street, and using extremely telephoto lenses with focal lengths up to an insane 2,400mm.

The only time the camera wasn’t on a tripod was for a few select Steadicam tracking shots, which moved with the characters and were also skillfully captured with a telephoto lens.

They maximised the number of shots in these public scenes, and covered the perhaps less accurately repeatable performances of the non-professional actors, by shooting with 2 cameras at a time.

This gave lots of foreground crossing through the frame, a compressed, tight, invasive, voyeuristic perspective and to get a feeling and energy of real people on the street reacting to what they thought were real situations rather than performed ones.

To me this long lens viewpoint also visually supports how caught up and focused the characters are on their own world and experiences. We care less about the outside world and more about the heightened individual emotions of the characters.

They shot digitally on a Sony F3 in HD on a flat S-log colour profile - with a desaturated look applied in the grade. They also placed diffusion filters in front of the lens to give the footage its soft, hazy look.

“We are so far away from the subject with the camera but with the sound you want the exact opposite. You want to be right up there with them. You don't want to feel as if you’re listening from far away. You want to feel as if you’re right in the middle of the action.” - Benny Safdie

This technique that they found on Heaven Knows What of balancing a far away, but tight visual perspective, with an intimate dialogue mix and dark, frenetic synth soundtrack became the backbone of their directorial style - and is a large part of what supports the chaotic, tense, heightened nature of the performances and story.

At this budget level, the Safdies leaned entirely into their strengths: realism, performance, and urgency. The lack of money forced them to abandon traditional coverage, elaborate lighting setups, or controlled environments, resulting in a film that feels dangerously alive.

GOOD TIME – MEDIUM BUDGET

With Good Time, the Safdie Brothers stepped into a more conventional independent film budget - but without abandoning their core aesthetic.

The increased budget, perhaps aided by casting Robert Pattinson in the starring role, allowed for a more structured production while still maintaining their raw energy. They were able to have a larger crew, legally secured shooting locations and execute more technically complex sequences.

Although the budget was larger, between an estimated $2 - $4 million, it was still very low considering the amount of locations and action sequences outlined in the script.

Once again, the starting point for the film came from the character - rather than the story and plot being the inception. They built Pattinson’s character by coming up with an extensive backstory, and drawing from emails he and Benny would exchange as if they were in character.

The Safdies also began leaning more heavily into genre. Good Time is structured as a one-night explosion of action, borrowing from crime thrillers and exploitation cinema, but filtered through their signature chaos and realism.

Although they had more resources to work with, they stuck with a similar independently minded low budget mindset when shooting.

“For the New World Mall we were able to get that location and secure that location. But we shot it as if we were stealing the shot. We still set up the cameras as if we were going to steal it when we ran in - so if we get caught we at least have the two shots. The cops were looking at us like ‘Why are you moving around so surreptitiously? You have the location.” - Josh Safdie

Again they worked with Sean Price Williams and again they used the same telephoto lens approach.

Like on Heaven Knows What they used an A and a B camera to maximise coverage.

With close framing that compressed space and isolated characters within crowded environments.

Often shooting from fixed positions on tripods with super long Canon zoom lenses. This look was paired with an alive and breathing handheld camera with Zeiss Superspeed primes. Or an occasional Steadicam shot.

At T/1.3 these fast primes, which let more light into the camera, aided them in exposing many of the darkly lit night time sequences.

This time, instead of using digital cameras, the slightly boosted budget allowed them to shoot on film.

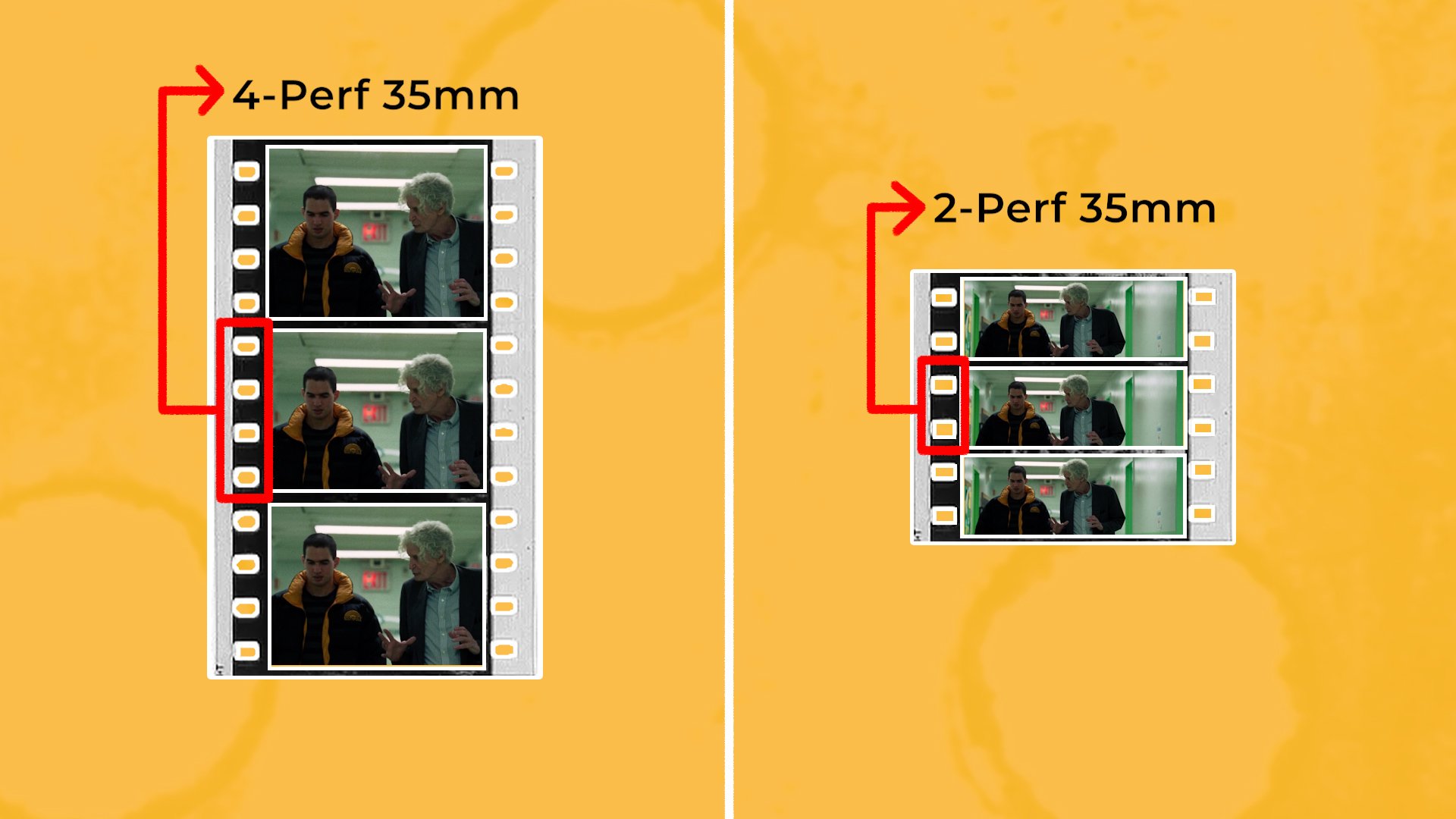

They decided to shoot 2-perf 35mm. This was done for a few reasons.

“With 35mm 2-perf we’re already degrading it a bit. Because if you shoot 35mm clean, after everything has gone through all the post processes, it’s so clean that it looks like you could’ve shot it on 4K or something. We like to try and maintain texture. So we did the 2-perf thing. Also it was for cost reasons.” - Sean Price Williams

Rather than the standard, taller 4-perf 35mm, 2-perf exposes frames with less height - which, when shot with spherical lenses, gives it an aspect ratio close to widescreen 2.39:1.

Because the surface area of the negative is smaller, it also means the film grain is more noticeable. With a more gritty texture somewhere between 16mm film and 35mm anamorphic.

Lastly, because it uses half the surface area of 4-perf, it is twice as cost effective. With less needing to be spent on purchasing film and developing it.

Unlike Heaven Knows What, Good Time uses light more expressively. He combined the real world neon signage, sodium vapour streetlights, and harsh fluorescents with RGB LED SkyPanels that his team set up. These saturated colours dominated the palette, creating a heightened, almost surreal nighttime atmosphere that visually added to the story’s chaos.

The additional budget allowed for set pieces that would have been impossible earlier: escapes, police chases, and more controlled stunt work. However, these moments are still shot in a way that feels frantic and unstable, often denying the audience clear spatial orientation.

Good Time feels like a bridge film - combining the raw aesthetic of their early work with the narrative propulsion and technical ambition of a larger production.

UNCUT GEMS – HIGHER BUDGET

After many years, that first film that Josh Safdie was researching in the diamond district before they shot Heaven Knows What, called Uncut Gems, finally entered production.

“10 Years ago when we set out to start this project, we wrote the first draft 10 years ago, one of 160 drafts, a couple of things never changed. One, Howard’s fate. The general plot of this basketball player with this gemstone was kind of always there, in that shape. And it never was a diamond.” - Josh Safdie

With a larger cast and more famous faces, it represents the Safdie Brothers operating at their largest scale while still resisting traditional Hollywood polish.

The film is far more expansive in scope, featuring numerous locations, set pieces and elaborate crowd scenes. Yet, despite the budget increase, the Safdies refused to smooth out their style.

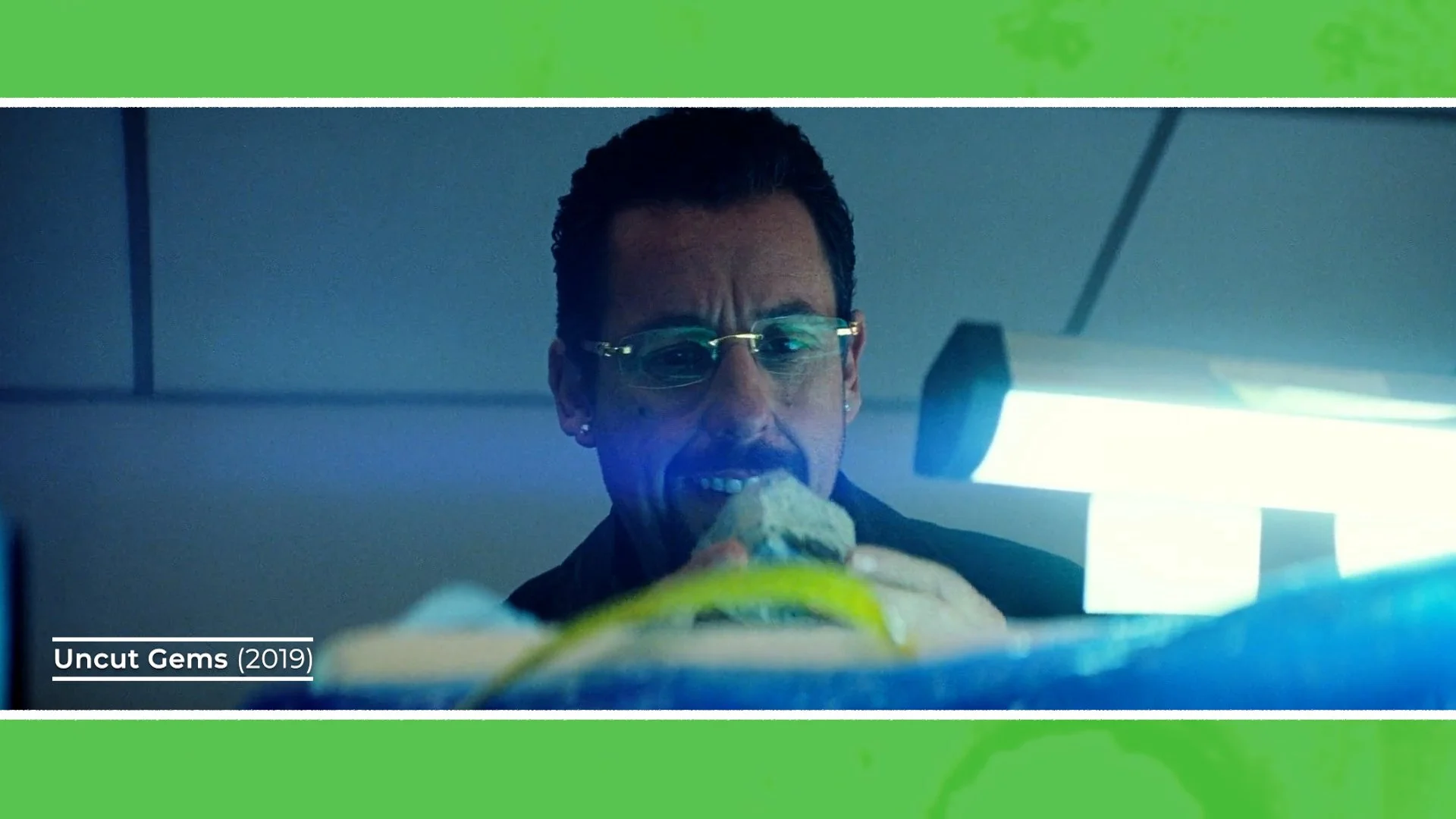

Shot again on Kodak 500T 35mm, this time by famed DP Darius Khondji, the movie embraces a similar abrasive visual approach.

However, this time using a slightly more mobile camera that often glides along on a Steadicam rather than being stuck in one place on a tripod.

They elevated their camera package by choosing to film in 4-perf anamorphic, rather than 2-perf spherical. This format gave the filmmakers a larger than life dimensionality which they felt was especially necessary for Adam Sandler’s close ups. The more expensive 4-perf anamorphic also came with a cleaner, tighter grain structure.

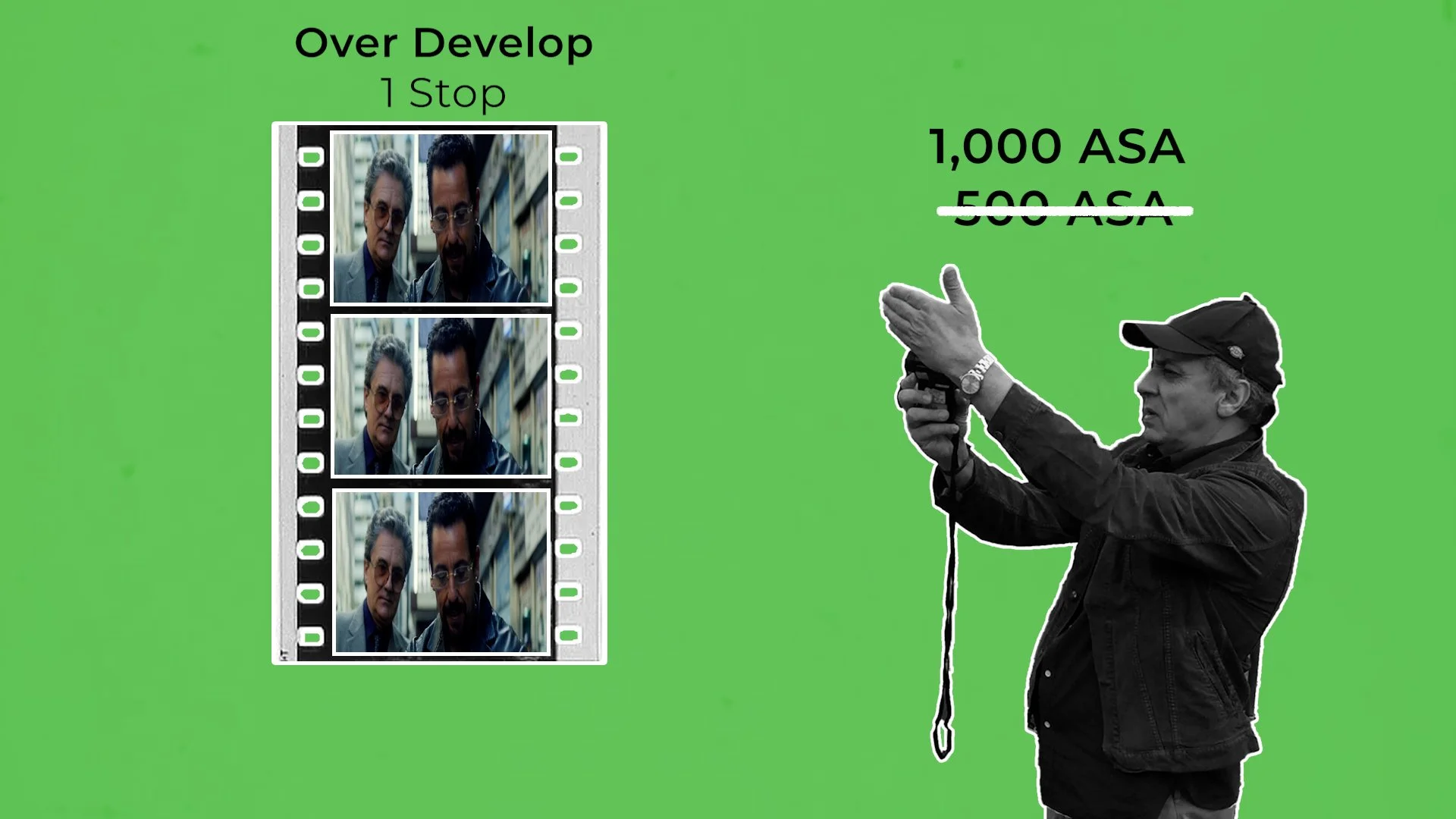

So, to get back a little more film grain, they decided to push process the film for one stop over the whole movie.

This is a technique where you intentionally underexpose film (by metering the 500ASA film at 1,000ASA) and then overdevelop it in the lab for longer than usual to compensate.

Again they went with long lenses. This time C-Series anamorphics from Panavision which included 180mm, 250mm and 360mm focal lengths, as well as telephoto zooms.

The long lenses compressed space, made backgrounds feel oppressive, and like characters are constantly boxed in by their environments - which added to the tension.

Lighting is perhaps a little more controlled than in Good Time, but still intentionally harsh and mainly done with practical lights that can be seen in the shot. Jewellery stores are flooded with artificial light and garish colour, RGB light pulses in clubs, work is done under vivid cyan practicals, and dark night exteriors buzz with colour and noise.

The camera remains restless, often hovering inches from faces, refusing the audience relief. The editing is aggressive, with overlapping dialogue and relentless pacing pushing the film toward sensory overload.

Where the budget truly shows is in logistics rather than style: closing streets, getting cameos from celebrities, staging major basketball games, coordinating large crowds, and executing complex sequences with precision - all while maintaining the illusion of chaos.

CONCLUSION

The Safdie Brothers are filmmakers who have maintained a remarkably consistent creative philosophy across every budget level. With street casting, telephoto lenses, intimate dialogue and chaotic plots.

At low budgets, limitations pushed them toward radical realism and raw intimacy. At medium budgets, they embraced genre while refining their visual language. At higher budgets, they expanded scale and complexity without losing the tension, chaos, and discomfort that define their work.

Rather than using increased budgets to smooth out rough edges, the Safdies use money to intensify their ideas - making their films louder, denser, and more overwhelming.